As per the 2021 CAG report, groundwater extraction in India increased from 58% to 63%, between 2004-17, exceeding the groundwater recharge rate. Climate change effects such as intermittent rainfall further alters the recharge potential, posing a huge threat to groundwater availability and quality. Recent assessments by the Central Ground Water Board (CGWB) show that many regions are overexploited, and a majority were also reported as critical and semi-critical.

According to the World Bank Report, 2012, India is the world’s largest groundwater user, estimated at 230 cubic kilometres per year − over a quarter of the global total. It serves about 80% of domestic water supplies and 45% of irrigation water requirements. Over extraction at the current rate can make nearly 60% of India's aquifers critical and threaten nearly 80% of drinking water over next two decades. This impacts equitable, healthy, and pollution-free access to water resources and therefore hinders the ‘right to water’ for current and future generations.

As of now groundwater is regulated in a piecemeal manner. This happens because states as trustees of groundwater fail to adequately implement laws on groundwater exploitation, poor aquifer management, contamination, etc. Socio-political dynamics and lack of sufficient monitoring add to this problem. Considering the total monitoring points and land area in India, only one CGWB monitoring unit is available for every 100-150 square kilometres. Sustainable policies, robust monitoring systems and comprehensive legal frameworks considering climate change risks are the need of the hour to tackle these urgent groundwater challenges.

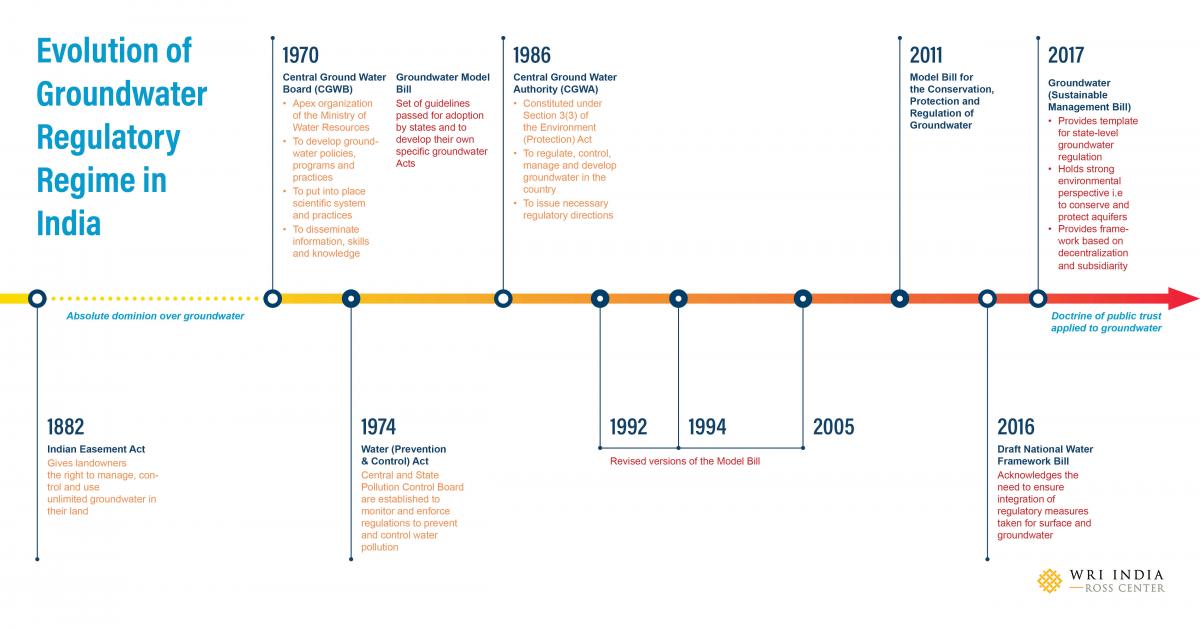

Legal framework in India does not explicitly define groundwater ownership and rights. Groundwater rights are still determined by the archaic Indian Easement Act, 1882. These rights tied to land ownership rights exclude a large part of the society that has no land rights and gives landowners the liberty to withdraw limitless water. This, in turn, leads to violation of fundamental right to water and the right to life (Article 21), failing to protect groundwater as a common pool resource. However, this has changed over time (Figure 1).

The CGWB was formed in 1970 specifically to develop groundwater policies and programs. It was later empowered by the Environment (Protection) Act in 1986 to form the Central Ground Water Authority (CGWA). Under this groundwater was acknowledged as a public resource supporting various legal actions such as the 2004 Supreme Court judgement highlighting the ‘public trust doctrine’. This judgement also reiterates to the government institutions to safeguard and ensure public access to groundwater.

CGWA is also authorized to declare certain zones as ‘notified areas’ with stringent regulations such as issuing No Objection Certificates (NOCs) and restricting energy use to extract water. The top-down approach of groundwater management failed to establish a behavioural transition among its users. People are crucial in maintaining the common pool resource nature of groundwater and to protect it against climate change impacts.

The first Model Groundwater Bill passed in 1970 was revised in 2011, 2016 and 2017. These bills empowered the state groundwater boards to create laws, manage water allocation and other relevant issues. The state boards and acts fail to efficiently regulate the haphazard groundwater extraction because of being understaffed, lacking expertise, and prioritizing socio-political conflicts over groundwater resource. They also focus more on regulating industrial groundwater extraction over domestic and irrigation sectors. These sectors are equally important to be monitored considering their significant share in India’s groundwater extraction.

The guidelines laid by the CGWA to regulate extraction, contamination and NOC renewals are the major contributions towards sustainable groundwater management. The National Green Tribunal (NGT) directed the CGWA to ensure that every individual and industry obtained permission for extraction. Groundwater contamination lacks uniform guidelines and is treated through case-based court proceedings such as the ‘polluter pays principle’. Climate change also poses a challenge in maintaining groundwater quality through altered recharge patterns and aggravated impacts of land use practices. Regulations should address both prevention and remediation of contamination for providing potable water.

The Model Groundwater (Sustainable Management) Bill, 2017, addresses some of the major concerns in the existing regulatory framework and offers a holistic way forward. The major highlights include:

Acknowledging groundwater as ‘commons’ is an important step in the right direction. Adequate regulations and sensitization programs will make groundwater visible to its users. Behavioural shift will help reduce overexploitation and balance aquifer protection. All states, as trustees of groundwater, should pass acts to realize the Model Bill 2017 guidelines. Legal frameworks with stringent regulations and monitoring of groundwater extraction, contamination and recharge can reverse the damages. It will also help in sustainable groundwater management, protection against climate change impacts and assured access to groundwater for all.

Views are personal.

The effects of the climate crisis are becoming increasingly clear in Indian cities. But how this crisis, and other environmental and ecological factors are experienced by different people and communities within cities varies greatly depending on a range of social, economic, political, and cultural factors. Read here.