In 2006, the Government of India launched the accredited social health activist (ASHA) program, with the goal to connect marginalized communities to the health care system. We assessed the effect of the ASHA program on the utilization of maternity services.

We used data from Indian Human Development Surveys done in 2004–2005 and in 2011–2012 to assess demographic and socioeconomic factors associated with the receipt of ASHA services, and used difference-in-difference analysis with cluster-level fixed effects to assess the effect of the program on the utilization of at least one antenatal care (ANC) visit, four or more ANC visits, skilled birth attendance (SBA), and giving birth at a health facility.

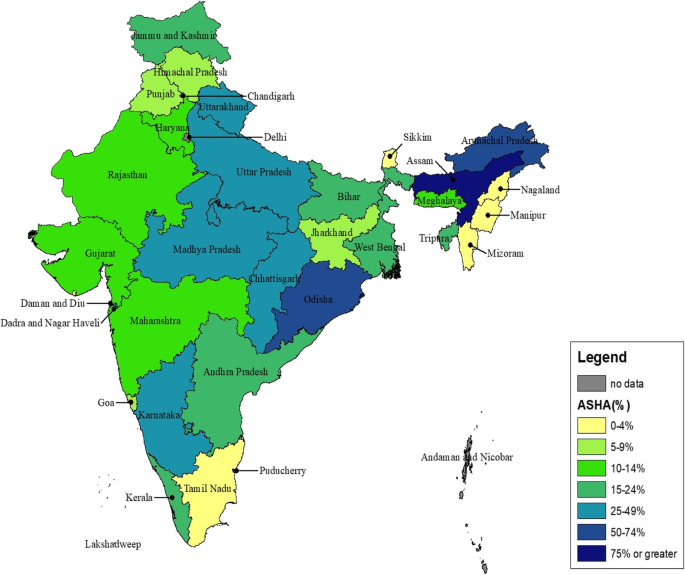

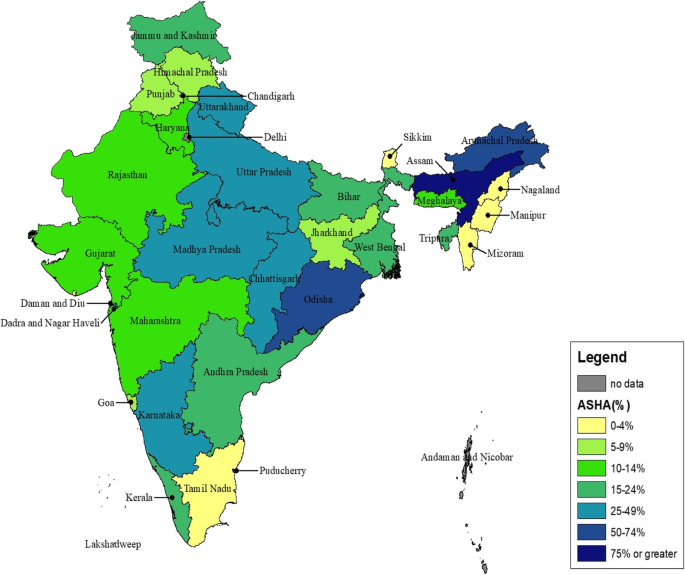

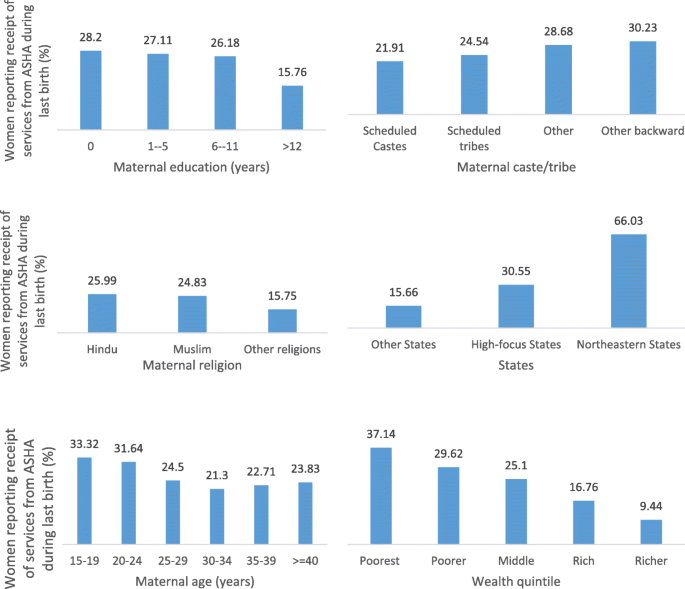

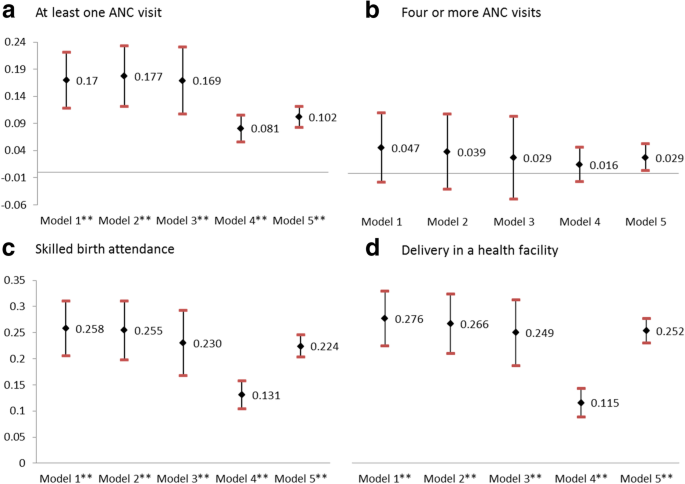

Substantial variations in the receipt of ASHA services were reported with 66% of women in northeastern states, 30% in high-focus states, and 16% of women in other states. In areas where active ASHA activity was reported, the poorest women, and women belonging to scheduled castes and other backward castes, had the highest odds of receiving ASHA services. Exposure to ASHA services was associated with a 17% (95% CI 11.8–22.1) increase in ANC-1, 5% increase in four or more ANC visits (95% CI − 1.6–11.1), 26% increase in SBA (95% CI 20–31.1), and 28% increase (95% CI 22.4–32.8) in facility births.

Our results suggest that the ASHA program is successfully connecting marginalized communities to maternity health services. Given the potential of the ASHA in impacting service utilization, we emphasize the need to strengthen strategies to recruit, train, incentivize, and retain ASHAs.

In 2015, India accounted for approximately 45 000 (range 36 000 to 56 000) pregnancy-related maternal deaths, making it one of two countries that account for one third of all maternal deaths globally [1]. Between 1990 and 2016, the maternal mortality ratio (measured as a pregnancy-related deaths per 100 000 live births) declined by 77% [1]. While some progress was made to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of a two-third reduction in maternal mortality, the target was not met and progress varied substantially across states [2]. Between 2005–2006 and 2015–2016, the coverage of four or more antenatal care visits (ANC) increased from 37 to 51%, institutional deliveries increased from 39 to 79%, and percentage of births with a skilled attendant increased from 47 to 81% [3].

A number of studies have demonstrated the positive impact of community health worker (CHW) programs on the promotion of reproductive health services and family planning, appropriate care seeking, antenatal care during pregnancy, and skilled care for childbirth [4,5,6,7,8]. However, there have also been several concerns about the performance and accountability of CHW programs, especially in programs scaled beyond the efficacy settings [9]. To date, most of the studies on the effectiveness of CHW programs have been small-scale randomized trials with interventions delivered under controlled settings; limited evidence exists on the effectiveness of national-level CHW programs. The WHO guidelines on health policy and system support to optimize CHW programs highlights the need for using longitudinal methods to assess the long-term impact of CHW programs [10]. India’s accredited social health activist (ASHA) program is the largest government-led CHW program globally with nearly one million trained CHWs.

In response to the relatively slow progress to strengthen maternal and child health, the Government of India (GoI) launched the National Rural Health Mission (NRHM) in April 2005. The NRHM is an ambitious effort to strengthen the national health systems and health care delivery, with a special focus on improving health care outcomes among the poorest populations [11]. The ASHA program, considered vital to the success of the NRHM, aims to increase community engagement with the health system and support access to public health services [12, 13]. The ASHA program was first launched in 2006 in 18 high-focus states—including 10 high-focus states (Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Jammu and Kashmir, Uttar Pradesh, Uttaranchal, Orissa, and Rajasthan) and 8 northeastern high-focus states (Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, Assam, Nagaland, Meghlaya, Tripura, Mizoram, and Sikkim). Within 2 years, over 300 000 ASHAs were trained and deployed at a ratio of one ASHA to 1000 population in rural areas. In 2009, the program was expanded to the rest of the country [14]. As of December 2015, there were 937 595 ASHAs operating nationally. Of these, 544 074 ASHAs are in high-focus states, 56 104 in the northeastern states, and 337 417 in other non-high-focus states [15, 16]. The ASHAs are an all-female cadre of CHWs, selected based on national guidelines by local village committees. Though they are considered volunteers, they receive some performance-based incentives. Although variations exist across states in the recruitment, training, responsibilities, incentives, and supervision systems for the ASHAs, there are some common guiding tenets. Table 1 summarizes their training [17], responsibilities specific to promoting the health of mothers and children [14, 18], and compensation structure [19, 20].

To understand whether ASHAs were differentially targeting any demographic groups within clusters where they are active, we restricted the analysis to only those 59% (n = 7985) of the clusters that reported an ASHA (Table 2). Compared to the youngest women ages 15–19 years, women in age groups 30–34, 35–39, and > 40 were significantly less likely to report ASHA services in the restricted sample. Within clusters with an active ASHA, compared to women with no education, women with 6–11 years and > 12 years of education were more likely to report receipt of ASHA services. This pattern was observed nationally, as well as when the sample is restricted to rural areas and to high-focus states. Compared to forward castes, women belonging to disadvantaged groups of OBC and scheduled castes are more likely to report ASHA services. However, no significant difference in receipt of ASHA services was observed among women belonging to scheduled tribes. Within clusters with an active ASHA, odds of reporting ASHA services declined steadily with increasing wealth status—nationally, in rural areas, and in high-focus states. No significant differences in the receipt of ASHA services were reported by religion across all groups.

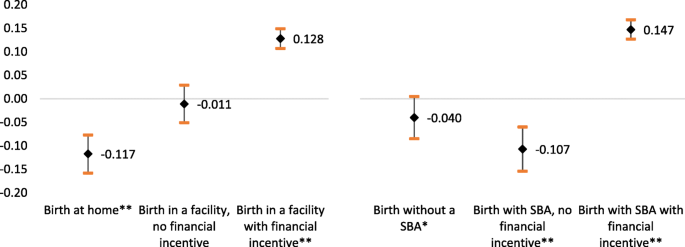

We attempted to understand the role of conditional cash transfers in motivating women to go to health facilities for birth and have a skilled attendant at the time of birth. Exposure to ASHAs is significantly associated with a reduction in home births, and births without a skilled attendant (Fig. 4). Exposure to ASHAs with financial incentives was significantly associated with a 12% and 15% increase in heath facility births and skilled birth attendance, respectively.

Exposure to ASHAs was strongly correlated with the utilization of maternity services. Even the most conservative assumptions for specifying exposure to ASHAs suggest that the ASHA program is associated with improved utilization of at least one antenatal care visit, skilled birth attendance, and giving birth in a health facility. The results also highlight the role of conditional cash transfers to incentivize facility-based births, and suggest that the presence of the ASHAs further augments this effect. The intent of the ASHA program was to reach marginalized communities—to connect communities that do not typically avail of services in health facilities to health care services at the community level. Our results suggest that the ASHA program is meeting these objectives as few programs have successfully done in the past.

While the ASHA program had the highest reach in the poorest populations, it does not address the disparities in the utilization of services across women from different socioeconomic and caste groups, especially the scheduled tribes. Historically, women belonging to scheduled tribes have minimal utilization of health services. For example, the National Family Health Survey (NFHS) reports facility-based delivery at 18% among scheduled tribes, compared to 33% among scheduled castes, and 51% among forward castes [32]. Our study indicates that utilization of maternity services continues to be the lowest among scheduled tribes, even after accounting for receipt of ASHA services. The tribal nature of these communities makes linkages to the health care system challenging and warrants further programming that is responsive to tribal customs around childbirth.

Prior process evaluations of the ASHA program highlighted several operational challenges. In several areas, the ASHAs do not receive timely payments for their services, which affects their performance [19]. Performance-based payments alone do not provide the financial security that is expected [33]. Studies conducted at the district or state level have reported that ASHAs may not be motivated in their role due to poor financial compensation [24, 34, 35]. Others have reported that ASHA activities in some states are hindered due to poor supportive supervision and mentoring structures [36]. Given our findings about the potential impact of the ASHA program on the utilization of services, especially for the marginalized, it is even more vital that these operational challenges are better understood and addressed. First, for the ASHA program to be sustainable, recruiting and training new ASHAs is as important as continued investments to ensure that the existing ASHAs have the institutional support and ongoing education needed to deliver the ever-expanding set of services expected of them. The effectiveness of large-scale mobile programs such as Mobile Academy for training of ASHAs should be robustly evaluated and, if effective, should serve as an adjunct instead of replacement for face-to-face instruction. Second, further research is needed to understand how the different implementation approaches, incentive systems, and support structures adopted by individual states have influenced the uptake and functioning of the ASHA program. Third, the role of the ASHAs in facilitating respectful maternity care needs to be further explored.

Contrary to the results of this study, a recent ecological analysis that explored the relationship between the change in proportion of villages within a district with an ASHA and a number of maternal health utilization outcomes, showed no impact of ASHA exposure on institutional delivery [37]. This study has several analytic improvements over the previous study in accounting for demographic characteristics which are established confounders of this relationship in the models, individual-level (instead of district-level) measurement of ASHA exposure and outcomes, and a longitudinal study design that accounts for targeting of the program by employing fixed effects methods at the cluster level. We assumed that accounting for cluster-level effects addresses variations in available health infrastructure thought of as critical to the success of the ASHAs. We used whether a woman received ASHA services as a proxy for whether the ASHA program was active in the area. By measuring ASHA exposure based on women’s self-reports, we capture functional exposure to the ASHA program. While this leaves room for measurement error in estimating the level of exposure, we account for this by presenting results from sensitivity analyses assuming a range of exposure definitions. Our study has some limitations. Seventeen percent of the households that were lost to follow-up in the IHDS-II survey were mostly urban, overall better-off households with higher levels of service utilization compared to the households that were part of both IHDS surveys. This limits the external validity of our findings. As with any non-experimental evaluation, our analysis is limited by unobserved factors associated with selective uptake of the ASHA program. Lastly, we are unable to disentangle the impact of the ASHAs from the impact of conditional cash transfers in driving the increase in SBA and facility births. Given that in most places the ASHAs bear the responsibility of informing women about the government’s conditional cash transfer scheme, we expect the impact of the two programs to be synergistic.

Our analysis presents an encouraging picture of the ASHA program 6–7 years into its implementation at scale. The ASHA program has increased in the utilization of antenatal care services, skilled birth attendance, and facility deliveries across caste, religion, and demographic groups. Most importantly, our analysis suggests that the ASHAs are more likely to reach groups that are typically left out of the formal health care system—poorer populations living in rural areas and women belonging to backward castes. The results of our study are promising given the sustained investments into the ASHA program by the national and state governments. However, the government needs to invest into supporting and increasing the reach of the ASHAs in marginalized regions with scheduled tribes. We emphasize the need to conduct ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the program to understand approaches to effectively scale the program and strengthen strategies to recruit, train, incentivize, and retain ASHAs.

In 2013, an expert consultation on the theme of CHWs in health care, organized by the United Nations Health Agencies (H4+) (UNAIDS, UNFPA, UNICEF, UN Women, the WHO, and the World Bank), highlighted the importance of CHW programs in strengthening national health systems and the critical need for identifying evidence-based interventions that CHWs can undertake in the reproductive health space. Identifying what interventions can be effectively delivered by CHWs would further strengthen the WHO and partner recommendations on task-sharing/task-shifting. This study addresses this gap by assessing the potential role of CHWs in effectively delivering maternity interventions and identifying the kind of interventions that are most likely to be affected through the engagement of CHWs. Historically, CHW programs at scale have not demonstrated the same impact as they have in controlled trials. Given the demonstrable impact of the ASHA program on the utilization of maternity services in our research, other countries and donor agencies can draw from the unique implementation features of the ASHA program in India.

Auxiliary nurse midwives